nature feature: mushroom undersides

For most, the word fungus evokes images of the gilled mushrooms that appear on our plates or pop up in suburban lawns. But, mushrooms are actually the tip of the fungal iceberg, so to speak. They are tiny reproductive outposts, incursions into the realm of sun and open air made by fundamentally subterranean organisms whose bodies are vast networks of filaments that burrow through soil and other decaying matter. In contrast to the well-defined mass of a mushroom, the size of a fungal network (the mycelium) is difficult to quantify and comprehend. A fungal mycelium can grow to fill its entire substrate which may be as small as a pile of dung or as large as a geographic territory. For instance, an Armillaria solidipes fungus in Oregon spans 3.4 square miles making it the world’s largest known organism.

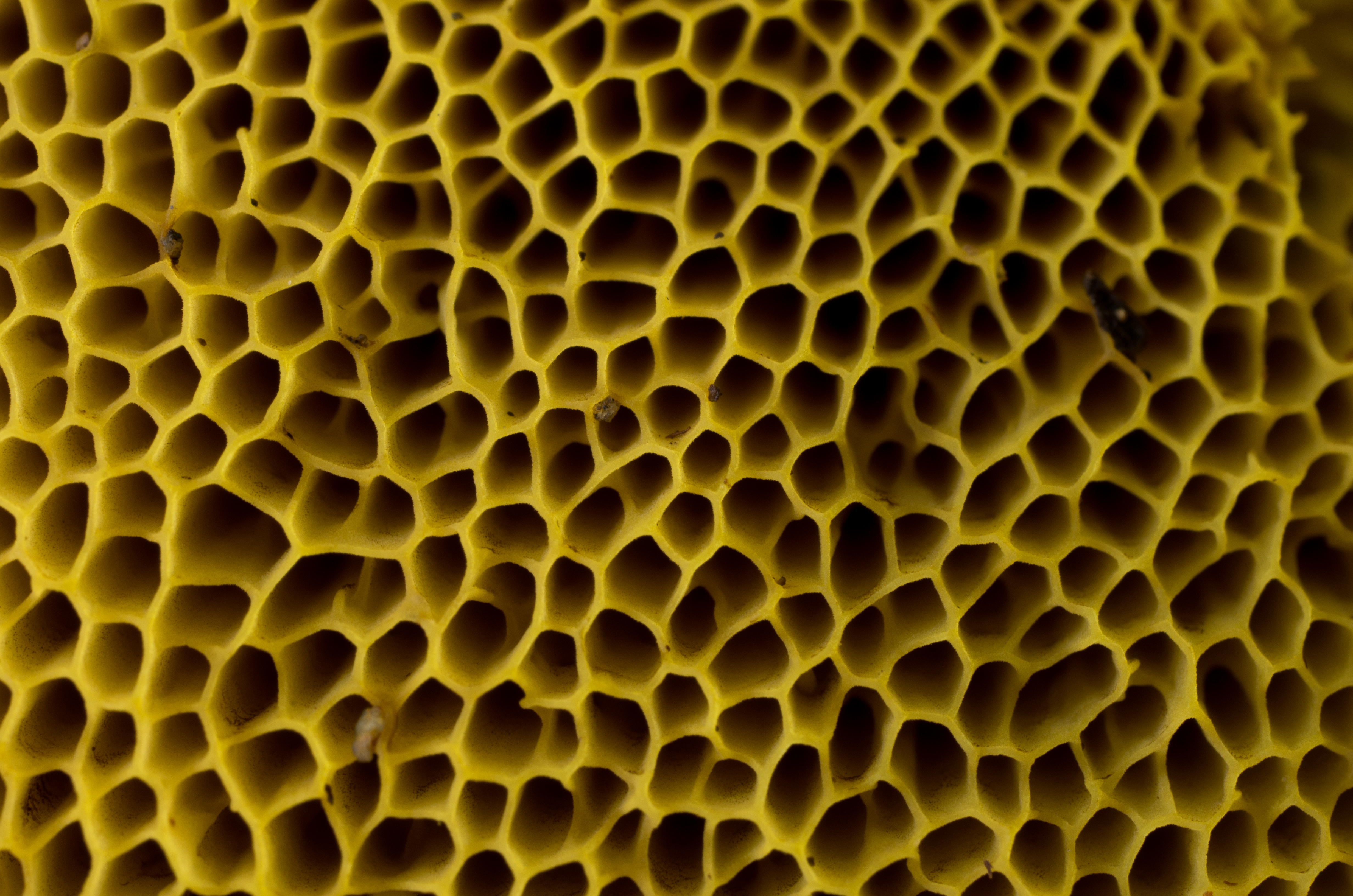

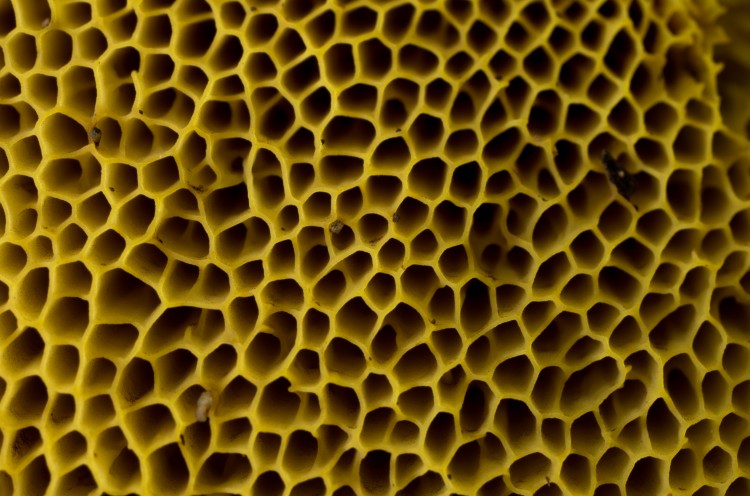

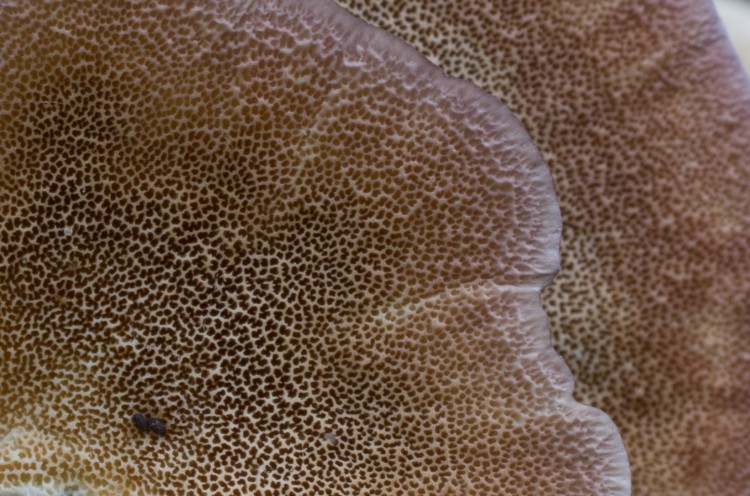

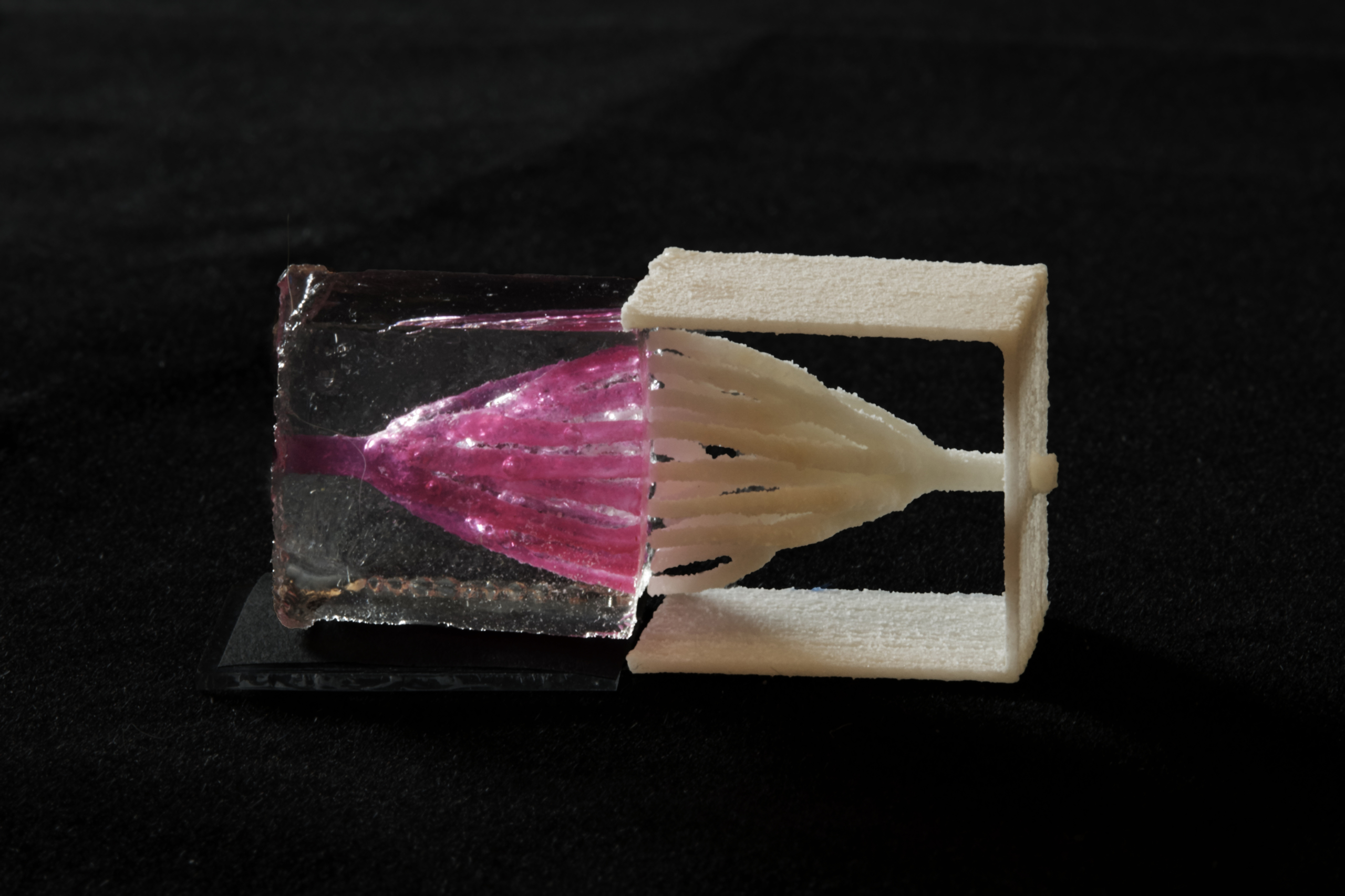

Umbrella-like caps shield fertile tissue beneath. This spore-bearing tissue (the hymenium) can be configured in a number of different space-filling arrangements from gills to pores to even teeth. All of these configurations succeed in creating a large surface area for spore production within the limited volume of the mushroom’s cap. A single mushroom generally fabricates and distributes over a million spores.

These photographs illustrate some of the patterns that structure the fertile surfaces of mushrooms. To me, the underside of a mushroom is considerably more fascinating than its upper.

Mushrooms are produced after the hyphae of two compatible fungi merge. Mushroom forming fungi are not classified as “male” or “female” as the mycelium lacks visible sex organs or characteristics. Instead such fungi are classified as having different “mating types” based on their genetic code at one or two locations in the genome. In contrast to our sex chromosomes which have two options, X or Y, these locations in the genome are often multi-allelic: they have many different gene variations. Rather than just two sexes, fungi species can have thousands of different mating types!

You can see some more of my fungal photography on flickr.

LuisRodriguez

Good to see that I am not the only one, that thinks that mushrooms are fascinating, inspiring and with incredible design patterns :)

Amy

When will you start making mushroom underside necklace pieces? Or earrings?

Jessica

we don’t have any plans to do that as of yet