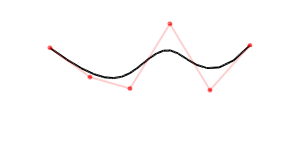

The other form of curve that processing supports natively is through the curve and curveVertex. These implement what are called Catmull-Rom splines, which we will discuss in more detail. This draws a smooth curve through the specified points. The curve command only supports four points, so to draw longer curves it is necessary to string several together or use curveVertex. The other caveat is that the first and last point of a curve only contribute to the tangent at the end points and do not get drawn. Commonly, this means that the first and last points must be repeated.

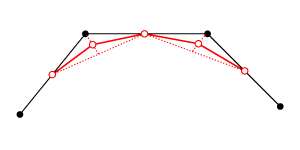

In more detail, for each segment of the polyline, you divide the segment in half. In other words, you make a new polyline that includes the midpoints of each segment. This gives us the same curve as before, just with more points. Then, the original points (not the midpoints) are moved to smooth out the curve. The only thing we need to know is where to move them. We want to move them inbetween their original positions and a position influenced by the midpoints. One way to think of this is to take the midpoint of the line between the new midpoints and use that as an approximation of the new point position. Then you average the original position and this approximation. Since the midpoints are just based on the original points, mathematically it is simple to describe the new point positions without referencing the midpoints.

These weights give the smoothest results; however, we could play with them to get different results. For closed curves, it might look like this in code.

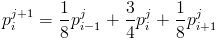

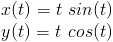

To draw our curve, we simply iterate over t and draw a vertex for each evaluation of our function. The smaller the step, the closer our lines will approximate the curve. As an example, a spiral can be defined as

which looks like

Parametric curves are convenient because they are simple to define, write down, and play with. It is also relatively simple to find their tangents. You simply take the derivative of each component (on paper). However, they are not necessarily intuitive to manipulate because they are mathematically, not geometrically based. I have included a simple library to define parametric curves, with text-based equation, which you can download here.

However, we want to make smooth curves. Most commonly, like all the default curves in Processing, people use degree 3 splines. Each degree of a curve can be interpreted as adding one degree of freedom. In our degree 1 case, each segment depends on two vector or end points. Phrased another way, we can draw a line between any two points. A degree 3 curves has two more degrees of freedom, so we can draw a degree 3 polynomial through any set of four points. However, our degrees of freedom do not have to be used as additional points, they can be any vector. For instance, instead of four points, we can specify to end points and the tangent each end point. From this, we get to the definition of Catmull-Rom splines, which is what Processing uses to draw curves.

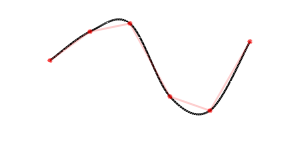

We define a Catmull-Rom spline by taking a polyline and setting the tangent or slope at each point. There then exists a unique degree 3 polynomial between every pair of points. The tangents will match up where the separate polynomials meet, so it will appear smooth. The only questions left are how to the tangent at each point, and what is the exact form of the polynomial.

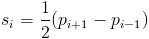

For a point p, we define the slope as half the next point minus the previous point. We can view this is the central approximation of the derivative at p

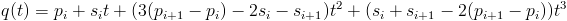

Now the polynomial between i and i+1 is

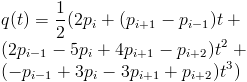

Or substituting in the points for slopes

For t between 0 and 1.

Often times it is desired to have more control over the shape of the curves, so it is possible to define a tension on each point. This is a scalar that we multiply the slope by. The higher it is the "tighter" the curve is. Sometimes it is also desired to normalize the slope by the distance between the points.

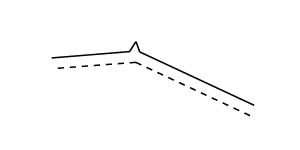

Non-Uniform means that the "parametric space" influenced by each point is variable. In the Catmull-Rom spline, the t is uniformly spaced between each point. It goes from 0 to 1. Or if we define it as a piecewise function, we could say it each segment goes from i to i+1. In NURBS, we can make this variable. We do so by defining what are called "knots". One of the most important roles that this plays is the ability to create cusps or sharp corners. By having the influence of point confined to a single parameter, we can create sharp corners.

Rational means we can assign a weight to each point. This is similar to the tension term in Catmull-Rom splines, but it is not applied to the slope. It is used whenever a point is used in computing the spline.

Bezier Spline refer to the fact that the polynomial that is being used is similar in form to bezier curves. This refers to the specific use of what are called Bernstein polynomials. However, the important information is that bezier splines do not interpolate the points of the curve. They act as "control points" influencing the curve but the curve does not pass through them like in Catmull-Rom splines.

The reason that NURBS are so important in computer graphics is because they are easy to evaluate, and they can represent a wide variety of specific shapes. For instance, by using certain weights, it is possible to create an exact representation of a circle. We can also represent curve with creases without having to represent them as two separate curves. This simplifies many operations because it does not require special cases for different types of curves. Everything can be represented by NURBS and treated the same: lines, ellipses, smooth curves, etc.

I have provided a basic NURBS library, which can be used to create NURBS curves and surfaces.

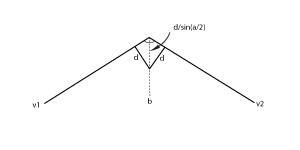

In a simple case we can define an offset polyline by creating a new point for each vertex such that it is some distance from the segments that touch it. This can be done through a simple formula shown that can be seen geometrically:

We can find the angle, a, between the vectors formed by those segments. We find the bisector of the segments by adding their normalized vectors. The distance along the bisector we find using the definition of the sin of angle. We can form a right triangle with the bisector, a segment, and a line of length d perpendicular to the segment. The distance along the bisector, d2, (hypotenuse) is d/sin(a/2). By adding our vertex and a vector along bisector of length d2, we get our new point. There are two problems we have to deal with: when we have a straight line and making sure we are offsetting to the correct side of our line.

Accordingly people have spent much effort developing robust offseting algorithms. One fairly easy way to get an approximate curve for an offset is using implicit surfaces. We define a function that it is greater than 0 within some distance d of the curve and less than 0 outside this area. We can then use a simple algorithm such as Marching Squares (the 2D version of Marching Cubes) to get the shape. This method will account for all degenerate cases, but it is computationally expensive and inexact. Depending on the application, you may also want to run a simplification/smoothing step afterwards to remove the stepping and straight segments from the results of marching squares.

The simplest way to represent a surface is as a grid of points. Then we just draw a rectangle (which is two triangles) for each grid cell. This only works for surfaces that can be structured as a grid. This is the most direct analogy of our polyline. If a polyline is a one dimensional array of points, then a surface is a two dimensional array of points. Many surface methods, such as NURBS, are based on this type of representation. Often times, you want a more general way to represent a surface. These are generally called meshes.

There are many ways to represent a mesh. The simplest is just a list of faces and each face has an ordered list of vertices. However, this does not tell us any connectivity information. Often times you desire to know which faces are adjacent to each other or what faces a vertex belongs to. Also, each vertex belongs to multiple faces. For a compact representation and one that is easy to modify, you do not want that vertex to be stored separately in each face. Otherwise, you would have to modify every face to change one vertex. Creating good mesh representations not straight forward, so there are several methods ways to do it.

One common mesh structure is called a half-edge mesh. In this data structure, each edge is represented by two objects (half edges), one for each face that the edge borders. Half-edges are directed and the two half-edges that represent an edge (pair) point in opposite directions. Each half-edge (he) stores four pieces of information:

- The vertex at the end of the he

- The opposite pair he

- The face that includes the he

- The next he in the face

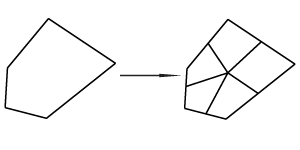

We determine the position for the point in the center of a face (face point) and the positions for the points that divide each edge in half (edge points). Then update the position of all original vertices.

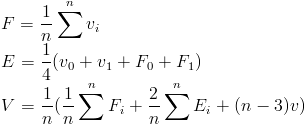

The face point equals the average of the vertices of that face. Each edge point equals the average of its end points and the face points of the adjacent faces. The new position of the vertex with n adjacent faces is the average of all the adjacent face points plus twice the average of all the adjacent edge points plus (n-3) times the previous position. This is normalized by dividing by n. In equation form

There are other types of subdivision schemes. The other most common one is called Doo-Sabin. For each face and vertex, it makes a new vertex, getting rid of the old vertices. This creates a new face for each vertex, edge, and face. The new vertices are created by a weighted average of the points of its face, .5 times the original vertex, .125 times the adjacent vertices, and 1/(4n) times all the vertices of the face (including the original and adjacent).

Though those two schemes are the most common, there exist many more. In fact, with these two as examples, you can sort of just start making them up. Some schemes have more limitations, such as only working on triangles. For open surfaces, you must modify all these schemes to account for boundaries.

When we generalize Catmull-Rom splines to surfaces we get what is called bicubic interpolation. The spline was an implemenation of cubic interpolation, so when we do it twice it is called bicubic. We do cubic interpolation in one direction, which gives us a set of points to do cubic interpolation the other direction. Because cubic interpolation requires four points, the first step has to use cubic interpolation four times for the four points. It looks like this NURBS curves can be extending to surfaces in a similar manner. However, the power of this representation for surfaces in not in working with a 2D array of points, but being able to use more abstract surface construction methods. For instance you can loft multiple curves together to get a surface. The reason this is possible is due to a technique called knot insertion. This amounts to increasing the number of points used to represent a curve without changing the curve. This way you can take curves defined with different amounts of points, match them up, and use the resulting points as a new surface. We can also create other more complex surfaces such as swept, extruded, or revolved surfaces.

facet normal nx ny nz

outer loop

vertex v1x v1y v1z

vertex v2x v2y v2z

vertex v3x v3y v3z

endloop

endfacet

OBJ files can support faces with an arbitrary number of faces. They also implicitly store connectivity information. Instead of storing each vertex with the face, first all the vertices are declared, then faces are defined by referencing the index of the vertices. The indices are determined by the order of the vertices starting with 1 (not 0 like arrays). An example of triangle would be:

v v1x v1y v1z

v v2x v2y v2z

v v3x v3y v3z

f 1 2 3

There are libraries to export OBJs and STLs, but sometimes they do not work as you would like. For instance, the superCAD library only support using beginRaw, which means if you want to export faces with more than three vertices it will not work.