Becoming Lichenized

Recently, my friend Shaunalynn Duffy asked me to give a talk at a Sprout event centered around Fungi. Specifically she was interested in the photographs of lichen I’ve taken over the past couple of years. I decided to speak a little about why I find lichen so fascinating and below you’ll find some of my thoughts in the matter. At the end, I include a brief aside on how our architecture should start being lichenized.

Why I like Lichen

Cladonia rangiferina, photographed in the Adirondacks, NY 07/11/2011

Lichen are strange conglommerations of two or more species from completely different biological domains of life. A lichen usually consists of a fungus and one or more photosynthesizing partners, usually it’s partnered with a single type of algae but sometime it can be paired with multiple types of algae or even cyanobacteria (photosynthesizing bacteria). Most fungi are decomposers, they feed on the detritus of other living things like leaves, soil and the dead. They live their lives in the soil hidden from observation except occasionally when their reproductive organs emerge for brief gaudy fits of spore dispersal. Fungi live inside their food. Their body is a huge absorptive mass of long linear branching cells called hyphae which provide them with a really big surface area to absorb nutrients from the soil. They typically do not build any complex structures, tissues or organs except when they need to reproduce; then they may build odd fruiting bodies like mushrooms to spread their spores. The shapes of these structures are adapted to their environment and it’s inhabitants who they must depend on to carry their offspring to new sites.

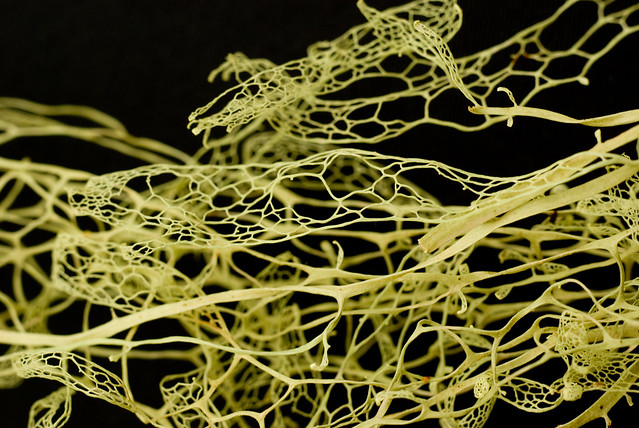

Ramalina menziesii, photographed at Drakes Estero in Point Reyes, CA 09/04/2010

But, lichen are different. When fungus partners with a photo synthesizer, it undergoes a dramatic transformation in physiology, chemistry, and life-style. While fungus is comprised of one large, simple structure of filamentous hyphae, lichen develop a myriad of complex structures to perform a variety of function. While fungus live as decomposers, the last step in a richly developed ecosystem, lichen are colonizers: some of the first organisms to enter desolate and dangerous environments such as toxic slag heaps. They have developed unique chemical pathways that can breakdown rock or oil.

Rhizocarpon geographicum, photographed at Glacier National Park, MT 07/15/2009

Some people describe a lichen as a fungus that has taken up farming, growing sugars in little algae patches throughout it’s body, in contrast to the decomposing habits of normal fungi. If fungi can be described as living inside their food, then lichen are essentially fungi turned inside out. Their food lives inside of them.

But I find it more intriguing to think of lichen as a fungus trying to be a plant. Like a plant it has photosynthesizing portions which produce food (the algae or cyanobacteria) but also structural components (the fungi) which protect and arrange the photosynthetic elements. As a photosynthesizing organism, lichen are under a lot of the same constraints as plants. They have to effectively collect sunlight and water. They have to be rooted to something, they have to resist gravity… Correspondingly, lichen have independently evolved very similar body plans to plants…..despite have an entirely different chemical and biological makeup.

crusty: photographed at Yellowstone National Park, WY 07/20/2009

leafy: photographed at Woodstock Land Conservancy, NY 12/24/2006

branchy: photographed at Yosemite National Park, CA 01/31/2008

Lichens tend towards three general body plans: crusty, leafy and branchy or crustose, foliose, and fruticose as they are usually called. But often a single lichen specimen may exhibit several of these morphologies as well as other less commonly seen ones. There are scaly lichens, powdery lichens and even gelatinous ones! But in all these body plans, the fungus must build transparent greenhouses of fungal tissue which protect the algae from UV light while displaying them in a way that allows light to be collected. They have to prevent the algae from dehydrating while allowing for carbon dioxide to diffuse into the algae during photosynthesis. These tasks are much more diverse from the normal role of fungal hyphae, which must simply spread out through the soil, exploring and absorbing food and this leads to much more morphological differentiation.

Cladonia Cristatella at the Woodstock Land Conservancy, NY

What about reproduction though? How can a lichen, which is actually a symbiosis of multiple types of creatures produce more of itself? Reproduction is complicated for lichen. Only the fungus can reproduce sexually, sexual reproduction for the algae is suppressed. The fungus produces spore dispersing structures. One of the most common seen among lichen are apothecia, these are the cup and disc-like growths you see in many of my photos. They can vary in size from under a millimeter to over 2cm. Sometimes they are the same color as the rest of the lichen other times they are dramatically color. Sometimes they are spread throughout the body of the lichen other time they protrude outwards on long stalks up to 1cm long.

left: lichen at Indian Lake in the Adirondacks, NY 7/21/2010

right: lichen at Fjordland National Park, New Zealand 08/28/2008

So the fungus produces these structures for the dispersal of spores but without an algal partner these spores can’t produce a new lichen. This means that if the spore lands somewhere where there happens to be some free living algae of the right species it might be able to lichenize and survive but most algae that form lichen can’t live in their environments outside of the lichen thallus (body). To get around this constraint lichen have developed several types of propagating units they can disperse that contain both fungus and algae. Also many can produce simply through dispersal of the lichen thallus; it a bit rips off and lands somewhere else, it may take establish a new lichen.

lichen photographed at Fjordland National Park, New Zealand 08/29/2008

Becoming lichenized

towards a new architecture

Fungi have incorporated algae and other photosynthesizers into the structures they build to provide themselves with a dependable sun-powered energy source. They’ve become lichenized. We should too.

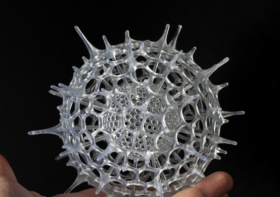

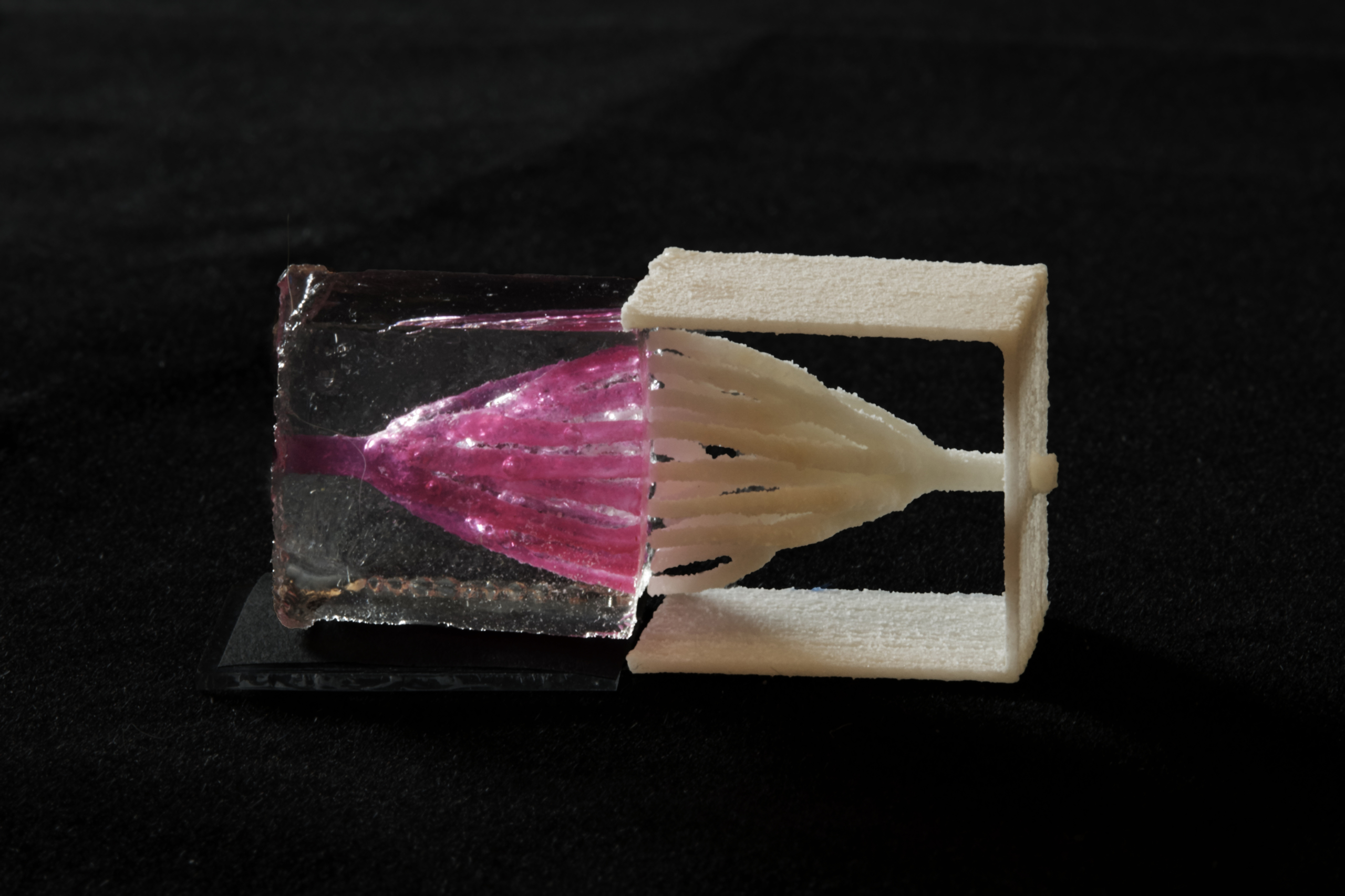

What would happen if our buildings became “lichenized”? As our knowledge of biotechnology and our environmental concerns continue to expand, we should take inspiration from the adventurous fungi and consider how we can better partner with photosynthesizers. How can algae or cyanobacteria be used in architecture to provide energy for our building systems? The self similar body plans of lichen and plants already inform us of many solutions to problem of how to compactly array photosynthetic cells to the sun. Research into biophotovoltaics or “Microbial solar cells” suggests we may be able to harvest electricity from photosynthesizing cells directly in addition to producing a range of useful chemicals and fuels.

Photosynthesizing surfaces offer many benefits over photovoltaic cells. The a biofilm of algae is a self-organizing, continuously growing system; hence it can self-repair leading to less maintenance and greater performance over a longer period of time. Photosynthetic systems have intermediate energy carriers which means energy can still be generated in the dark. Photosynthetic systems have a vibrant aesthetic appeal, by adding them to our buildings and cities we’d be “greening” them.

So what happens when our built environment becomes lichenized? As with the fungus whose structure and lifestyle change so dramatically, how can our buildings, urban planning, and society change when we are freed from the grid of infrastructure that currently supports, but also limits us.

Interested in this? Here are some articles I found interesting. Please send more my way if this is your area of interest because I would love to learn more.

Microbial solar cells: applying photosynthetic and electrochemically active organisms

Direct Extraction of Photosynthetic Electrons from Single Algal Cells by Nanoprobing System

Development of Bio-Photovoltaic Devices

Jasj

Hello Jessica,

you might like http://www.plant-e.com/ , it is a Dutch startup working on extracting electricity from plants. Their ideal is to have plants generating electricity on every roof!

Jer Thorp

I love this post.

My mother is a textile artist and when I was young she did a lot of experimentation with lichens as natural dyes. Whenever we’d go on walks through the forest, I’d always be keeping my eyes out for different kinds of lichen – from the huge clumps of Old Man’s Beard to the more ornate and colourful species that grew all throughout the understory. British Columbia was a good place for lichens!

Carl Swanson

Great Stuff about a good idea – very intriguing

Lucy Carty

What a wonderful and intriguing article – beautiful photos too. I’m sure the guys at http://www.institutewithoutboundaries.com would love to hear your ideas on lichenized architecture and urban planning…

Looking forward to your next post!