creature feature: sponges

Sponges are my latest creature obsession. While they are technically animals, they lack many of the fundamental features that distinguish animals from other lifeforms. Their bodies are asymmetrical and amorphous. Their cells, while organized are not structured into tissues. They have no organs, no respiratory, digestive, or nervous systems. Let me be frank here, they don’t even have a mouth or an anus.

Stranger yet, if you take a sponge apart, cell by cell, by straining it through a sieve; the cells can reassemble themselves into a new sponge (video here). No other animals can do this. Sponges seem to be what happens when unicellular creatures evolve the ability to stick to each other: they function as a unit, but their aggregation is more or less non-specialized and reversible. While we often think of creatures as either unicellular or multicellular, sponges seem to fall somewhere in a grey zone between the two lifestyles.

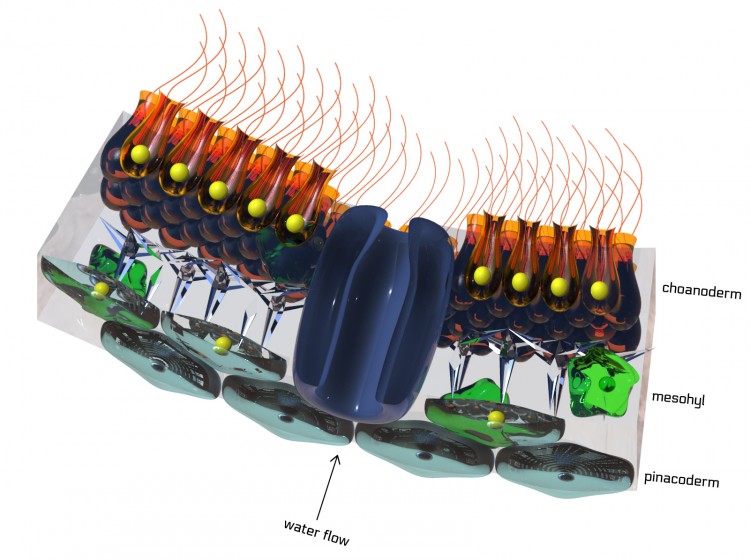

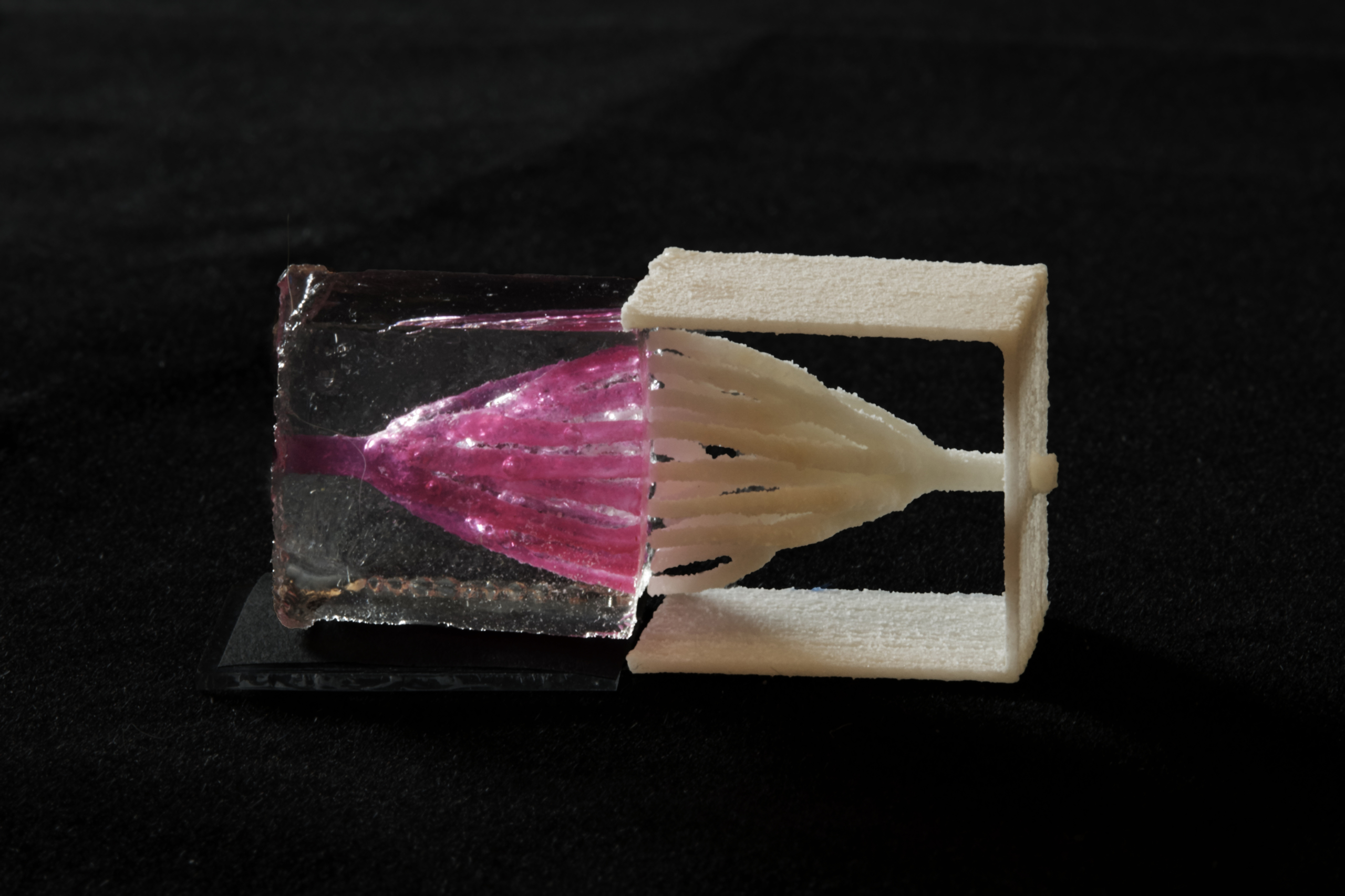

Sponges are sessile filter feeders. They primarily sustain themselves by digesting bacteria and picoplankton strained from the water around them. They do this through a clever and efficient arrangement of their cells into networks of canals and chambers that allow them to precisely control the flow of water through their bodies. They use the directional flailing of flagellated cells called choanocytes to draw water into small incurrent pores and then up through a hierarchical series of tubes and chambers where the water is slowed down to allow for digestion of suspended particles. After passing through the choanocyte chambers, the water is sped up and ejected at high speed so the sponge will not filter the same water again.

The exterior of the sponge is covered in pinococytes and the interior of the sponge is covered in choanocytes. Each of these layers is only a single cell thick. Between them is the mesohyl, a gelatinous matrix composed of collagen, fibrils, spicules (skeletal elements), and other things. The mesohyl is home to mobile, amoeboid cells that produce collagen and spicule structues. It is also home to the archeocytes, a special cell type that can differentiate into any other cell type and also plays a role in digestion and food transport within the sponge. These mobile cells are the ones responsible for reassembling the sponge in the experiment discussed above.

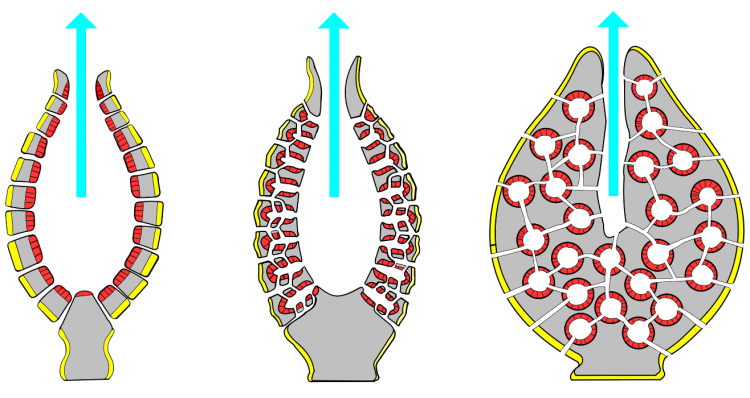

In the simplest sponges (asconoid), water enters through the porocytes into a vase-shaped chamber of flagellated cells. It exits through the top of the vase. In more complicated sponges, the cell layers are folded (Syconoid) or branched (leuconoid) to create more surface area for choanocytes. Leuconoid sponges can grow to several meters in size.

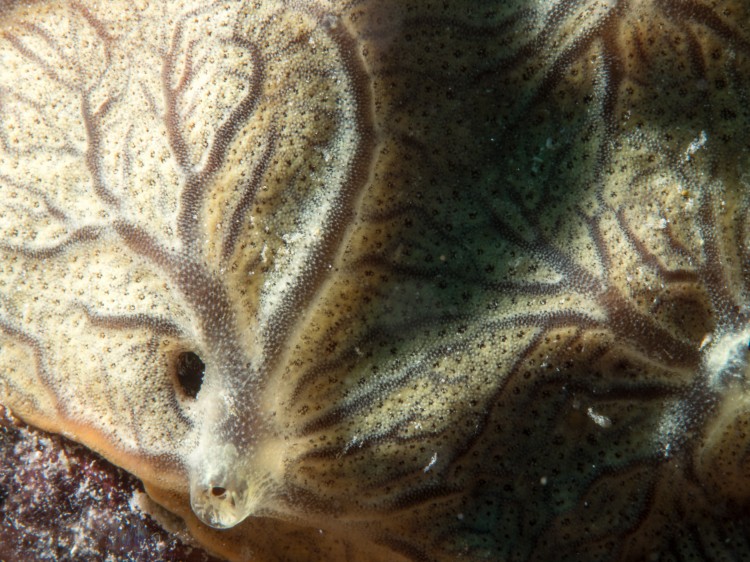

In January, we took at trip to Bonaire, an island in the Caribbean renowned in the SCUBA diving community for its pristine reefs. While there we observed dozens of sponge species. They stood out because of their intense coloration, textured surfaces, and overall strangeness. I’ve included a few of my photographs in this post. By far, my favorite sponges I documented were the encrusting types. They are fascinating because their excurrent canal system is exposed as a series of raised, radial branches terminating at a central exit hole.

Joel M

Truly great article. Amazing macro photos. It seems that you are in total control of your camera compare to the first post about underwater photography. Hope to see more marine photos from you!

Jessica

thanks! I just finished a trip to Jeju, Korea where we did some diving and I hope to post those photos next week.